I've signed up for edX's course

the Art of Poetry, taught by Robert Pinsky. (There is still time to sign up--it just started yesterday.)

I'm excited about it--immersing myself in poetry is what I planned to do with the next three or four months, and I have been diligently working on my own poems for a few weeks now. What perfection to have Pinsky's guidance and the inspiration of all the participants and poets whose work is featured in the course.

Part of the coursework is to present our own "anthology": favourite poems by other authors and what they mean to us. I present my first response here.

Last Look

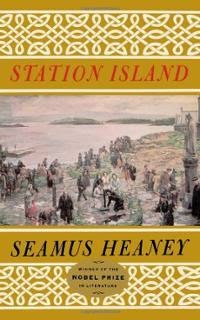

by Seamus

Heaney

In Memoriam

E.G.

We came upon him, stilled

and oblivious,

gazing into a field

of blossoming potatoes,

his trouser bottoms wet

and flecked with grass seed.

Crowned blunt-headed weeds

that flourished in the verge

flailed against our car

but he seemed not to hear

in his long watchfulness

by the clifftop fuschias.

He paid no heed that day,

No more than if he were

sheep’s wool on barbed wire

or an old lock of hay

combed from a passing load

by a bush in the roadside.

He was back in his twenties,

travelling Donegal

in the grocery cart

of Gallagher and Son,

Merchant, Publican,

Retail and Import.

Flourbags, nosebags, buckets

of water for the horse

in every whitewashed yard.

Drama between hedges

if he met a Model Ford.

If Niamh had ridden up

to make the wide strand sweet

with inviting Irish,

weaving among hoofbeats

and hoofmarks on the wet

dazzle and blaze,

I think not even she

could have drawn him out

from the covert of his gaze.

I am blown away by

this poem on so many levels. Each word is essential, and if stayed with a while,

brings me straight into the seedy physicality of this moment, and a wonderful,

halfwild physicality it is.

On first reading I

am swept away with compassion and sympathy for this old man who is looking out

over his world at his long ago life. Because I came from the Canadian prairies,

with strong connections to farms and farmers and old people whose clear

insistent ways were being—unbeknownst to me, who couldn’t understand their

aggravation—sheared away from their centrality in the world by the unhesitating

crush of change, I feel in my own body the empty-handedness of his loss.

Here of course I am

reading more into the poem than is actually stated. He may not feel loss, but I

do. I fought hard against the rigid thinking of my elders, even as I loved them

immensely and suffered unbearably under their disapproval of my “crazy” beliefs

and life. But at the same time I rose from these people just as this man rose

from the hills and roads and work that shaped him. Now that they are gone, and

I’m living in a world where few of my acquaintances knew or felt bonded to the people

and ways—much of which had great value to me even then—that I ran from and now have

lost, I find myself bereft, and longing for a visit home.

How often I am not

quite in 2014, standing instead gazing into 1963. When I read this poem I am

the gazer and the onlookers, both.

I love that the

onlookers are looking on. Though he

is by now a lock of hay on a bush, a small integral element of his environment,

he is real and current to them. They may not exist for him, but for them he

exists intensely; they witness him as I witness my elders and their vanished way

of life. Heaney and his unnamed companion have great empathy for the gazer, but

they are on the roadside, they are comfortable in now; they love the man of the

past and the present both at once.

It is with great

delight that I arrive at the final stanza, where Heaney reminds me of the

magical precedents of Ireland, of the queen of the Land of Youth who came from

the sea and enticed Oisín away to the Otherworld for three hundred years. She is

from a time far more ancient than the gazer’s cart and Model Ford, and she is

as much of him, more even, than she is of Heaney and of me.

“Last Look” is a trip

into a beloved past that is firmly rooted in today, tying both together with

the dancing power of a goddess on her horse clattering about the beach.

And even she can’t

flush him from the covert of his gaze. What a wonderful word! He is the hay, he

is the hills and cart, he is the bird of memory hidden in the brush.